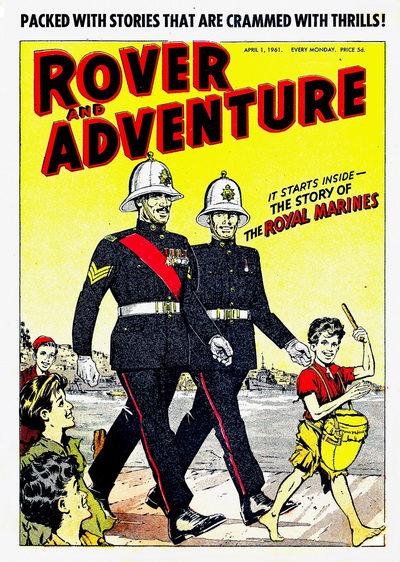

BRITISH COMICS

THE GOLD BADGE OF COURAGE

First

episode taken from Rover and Adventure

The story of Harry Clint, whose aim is to wear the badge of

|

Mr Towen, former Captain in the Royal Navy, rose early one morning. He

broke his normal habit of a cold bath and dressed at once, first strapping on

the false foot that took the place of the real one he had left at the He was heavily muffled against the cold, hands thrust deep into his

pockets and his nose red and glowing where it poked out from the space

between cap brim and muffler. He carried a shotgun in the crook of his right

elbow. “Morning, Bill,” answered Mr Towen. “I’m just putting the kettle on.

We’ll have a cup of tea before we start.” “There’s time enough, sir,” agreed

Bill. He took his hands from his pockets, leaned the shotgun against the

sideboard, then began to thaw his fingers over the electric fire. “It’s a

nippy one, right enough,” he remarked. “Cold and frosty,” said Mr Towen, now

busy making the tea. He produced a brew that was inky and strong enough to

stain leather. He poured it into two china mugs. They were sipping it, Bill contentedly

puffing evil clouds of smoke from a cracked briar pipe, when a step sounded

on the stairs. “Thought I heard someone moving around,” said Adam Towen,

appearing in the hall doorway. “What murky business are you two plotting?” “

’Morning, boy,” said Mr Towen, smiling at his son. “Bill hand me over another

mug.” “I say again, what are you up to?” said Adam, joining them at the

table. His father passed him a mug of tea. Adam sipped the rank brew,

shuddering as he did so. “Why this meeting in the early hours?” he asked. “We

have an intruder,” said Mr Towen, “a fellow with a habit of sneaking into the

ground in the early mornings and messing around. I’d have brought you in on

it, but I thought you might be tired after your journey.” “I’m too worried about

the result to be tired,” Adam replied, referring to the examination he had

sat in |

|

You’ll

find a selection of sticks in the hallstand.” “No gun of mine ever went off by

accident, sir,” Bill said reprovingly. But he laid his shotgun against the wall

and went into the hall. His voice drifted back, “I’m counting on this

trespasser being one of those young rips from the town. Might give him a bit of

respect if he had his tail peppered with smallshot.” “It’s a good thing I know

the kind heart that beats under that velvet waistcoat,” said Mr Towen, and was

still chuckling when Bill returned with a knobbly length of polished

blackthorn. “What-ho,” said Adam, following on the gamekeepers heels. “Are you

issuing all hands with cutlasses, Skipper?” “Just sticks,” replied his father.

“Grab yourself one and let’s go.” They left the house and drove through the

lanes in Mr Towen’s car. The darkness was giving way to the grey light that

comes before dawn. They reached a field close to the coppice and Bill and Adam

jumped out to open the gate so that Mr Towen could run the car in behind the

hedge. It was cold and the grass crackled frostily under their boots. “We’ve a

quarter of an hour to spare at least,” observed Mr Towen, switching off the

light ignition. “That’s providing he comes at his usual time.” “How do you know

what is his usual time, Dad?” Adam asked. “A lot of detective work,” Mr Towen

answered. “Bill and two under-keepers have been watching at night and during

the day, but still there’s been signs in the morning of the fellow’s visits.

Then one of the estate dairymen saw me yesterday and said that he’s seen a

cycle lying against the hedge on his way for the first milking every morning

this week.” “I still don’t see how you can tie the time so close,” Adam

frowned. “Bill and his crew come off duty at six and walk home along the lane,”

Mr Towen said patiently. “They didn’t see a cycle. Which means the villain must

arrive a little later.” “That’s Navy training for you,” Adam said admiringly.

“It gets the brain working like a clock.” “For that remark you can have the job

of laying an ambush in the coppice with Bill,” Mr Towen ordered. “Anyway,

you’re both nippier on your pins than I am with this set of tin toes. I’ll stay

out here and grab the cycle once he’s inside the wood.” “Supposing he don’t

come, sir?” said Bill. “Then the three of us have had the benefit of a couple

of hours in the fresh air,” said Mr Towen. “It will probably do us a lot of

good.” Adam let out a hollow groan, then he and Bill squirmed through a gap in

the hedge into the coppice. Mr Towen listened for a time to the sound of their

movements before closing the gate and returning to the car. “Now, why should

this ass visit the coppice in the early hours?” thought Mr Towen, working his

mind to take it off his discomfort. “Bill says there’s no sign of poaching, but

maybe this fellow doesn’t use the normal methods.” Time slowly passed and the

cold began to seep into his bones. Mr Towen huddled in his duffle coat. There

was no sound from the coppice, but he knew his son and Bill Perry must be

suffering in the same way.

THE WATCHERS POUNCE

Seven miles away, in a small house in the nearby town. Harry Clint was

just carrying a breakfast tray into the bedroom of his Uncle Zach. He and his

uncle were alone in the house and Uncle Zach was elderly, slightly sour, and

not inclined to bother with any housework that could be done by a healthy young

nephew.

Harry

laid the tray on a table and was rewarded with a stern glance from the bed.

Harry had brought in a cup of tea half an hour before and Uncle Zach was now

almost awake. “You’re late,” the old man said reprovingly. “It’s nigh on a

THE CHASE

He caught a glimpse of water among the thin boles of saplings ahead.

This was where he had to be careful, for he had to reach the edge of the bog at

exactly the right place. He veered a shade to his left and sighed with relief

when he came on his boot tracks of the previous day.

The

bog was some twenty yards across, a four-foot width of stream in the middle,

and scattered across it were logs that Harry had placed there for footing.

Harry well knew the location of each one and he went across without slacking

speed, merely fitting his stride to the varying intervals between the logs. He

reached firm ground on the far side and paused for a breather and to look back.

The man with the stick was tired and jogging slowly down the last few yards of

the slope. The other man, the younger one, was halfway across the bog, leaping

from log to log with the skill and timing of an athlete. Harry watched

expectantly. The young man reached the log at the edge of the stream and

bounded lightly across. That was where he came unstuck. The mud was deep and

liquid on the far side and the log placed by Harry was inclined to roll. Harry

had been braced for it, the other man was not. His foot shot forward, he

teetered backwards, lost balance and went into the stream with a startled howl.

“Wonder if he always goes swimming with his hat on?” chuckled Harry, trotting

easily up the opposite slope. He kept on through the coppice and emerged on the

lane a hundred yards from where he had left his cycle. He ran to the machine,

hurriedly pulled on his jacket. Then tried to mount and ride away. The result

was a horrible jarring and clanging. Harry stopped dead with a dismay similar

to that of the man who had fallen in the stream. “It’s no good, young man,”

said a quite voice. “I took the precaution of letting down your tyres.

CAUGHT!

A man came through a gate in the hedge on the opposite side of the road

to the coppice. He was a tall man with a weather-beaten face and keen eyes and

he seemed to limp slightly on one foot. Harry held on to the bike and felt like

a burglar caught in front of an open safe.

“You

shouldn’t have done that, sir,” he said, trying to sound cool. “Now I’ve got to

pump them up before I can get to work. “Bless me, you’re a cheeky ‘un,” said

the man with the limp. The amusement passed and his voice took a stern tone.

“My name’s Towen, and I’m manager of the private property in which you have

been trespassing. Is there any reason why I should not hand you over to the

police.” “I’d rather you didn’t, sir,” Harry said truthfully. “I guessed the

place was private, but I didn’t think I was doing any harm with a bit of

scrambling.” “Scrambling?” said Mr Towen puzzled. “I’ve charted out my own

course in there, sir,” Harry explained. “It’s just over a mile round and rough

going all the way.” “But, dash it, boy, why use private property for your

exercise?” demanded Mr Towen, staring at him. “Isn’t there any public place you

can go?” “Not round here, sir,” replied Harry. “Just a scrubby park and bit of

playing field in town. Outside it’s all farming country. I found this place on

my way home from work last week.” “What’s your job?” Mr Towen asked. “A

steelman, sir,” said Harry. “What you’d call a builder’s scaffolder. I’m

working on a repair job near here and I’ve been putting in half an hour on the

scramble there each morning.” “Most interesting,” observed Mr Towen, tugging

thoughtfully at his moustache. He asked more questions, doing it in a friendly

kind of way, and they were deep in conversation when two mud stained figures

came through the gap in the hedge. Angry cries filled the air on sight of

Harry. “Soaked to the skin,” snarled Adam Towen. “That fellow tricked me into a

ducking.” And Bill Perry added bitterly, “I got pulled in trying to help him

out. If I hadn’t lost my stick I’d lay it across that young man’s pants.” “Stop

fussing over a little water, gentlemen,” Mr Towen ordered. “This is my friend,

Harry Clint, who will be visiting us tonight to make a full apology for the

trouble he has caused.” “I’ll be there, sir,” said Harry, pumping air into his

tyres. Mr Towen drove the car slowly out on the lane and halted for his

dripping companions to clamber in. Harry had finished pumping his tyres. He

gave them a wave of the hand and took the bike away with a rush. Mr Towen drove

off in the opposite direction towards his house. “A man should try to learn

something new each day,” Mr Towen said thoughtfully. “I now know that steelman

puts up scaffolding about buildings.” “Interesting,” said Adam, his teeth

chattering with cold and damp as he shared a rug with Bill. “Dad, what’s the

idea of inviting that little squirt home?” “An unusual boy,” said Mr Towen.

“Undersized, scrawny, yet incredibly determined. He wants to become perfectly

fit, and I should like to find out why.” “He’s certainly plotted out a rough

scramble course,” said Adam, attempting to control his teeth and smile. “I mean

to take a closer look at it this afternoon.” “I should have thought you’d

looked close enough this morning,” Mr Towen said dryly, and even the glowering

Bill managed to raise a smile.

HARRY EXPLAINS

Mr Towen had doubts during the course of the day as to whether Harry

would turn up. The young fellow had been caught trespassing, an offence liable

to punishment by a fine. By

He

was surprised when Harry arrived at eight, and pleased when he realized the

extra time had been taken up by the boy going home to clean up and change.

Harry was now neatly dressed in a sports jacket and flannels. “The boy has

manners,” thought Mr Towen, shaking hands and leading the visitor into the

lounge. “I rather think you’ve met my son, Adam, Harry,” he said aloud. “At a

distance,” said Adam, returning Harry’s quick grin. “Sit down, Harry. I had a

go round the full circuit of your scramble this afternoon.” “It’s good

training, but not really rough enough,” said Harry seriously, sitting bolt

upright on the edge of an armchair. “It’s all wood and bog. It would be best

with a bit of rock scambling somewhere along it.” “You do like doing things the

hard way,” Adam said admiringly. “What’s the idea of it? Are you in training

for athletics?” Mr Towen, moving over from where he had been busy at the

sideboard, placed a tray holding glasses of fruit juice on a small table and sat

down. “I’m willing to give you permission to go on using my employer’s land as

a private exercise course, but I’d like to know the reason behind it,” he said.

“It’s just a hobby of mine,” said Harry, suddenly on the defensive. “It’s a bit

hard to talk about. “You’re among friends,” said Mr Towen, handing him a glass.

“You fire ahead.” “It’s a bit personal,” Harry said nervously. “I’m not too

strong and that isn’t very good in a tough neighbourhood like mine. Some

fellows are strong and clever enough to do things easy, but I’ve had to work

real hard at anything I wanted to do. That’s why I’m trying to build myself up

a bit.” He paused, looking embarrassed. “It happened when I was about twelve,”

said Harry. “I was mucking about in the town library and I came across a book

about the Royal Marines. I got so interested I was reading it when the library

closed. Since then I’ve read everything I could pick up about the Royals. The

petty-officer at the recruiting office lets me have any pamphlets he gets. Next

Saturday I’ll be seventeen, and that’s when I can volunteer.” He paused again,

this time because both his listeners had broad smiles on their faces. “What a

coincidence!” said Adam. “I’m also trying to join the Marines. I’m waiting for

the results of my exam to go up before the Fleet Selection Board.” “Crikey,”

said Harry stunned. “A blinking officer.” “Not by a long way,” laughed Mr

Towen. “Anyway, Harry, I’m delighted to hear your plans. You keep on using your

scramble course and just let me know if I can help you in any other way. Have

any of your family ever served in the Royals?” “No, sir,” said Harry. “Just me,

Harry the First.” “Here’s wishing you luck,” said Mr Towen. “As a matter of

fact it might do that son of mine some good if you dragged him scrambling in

the mornings.” “I haven’t dried out from the last lot yet,” Adam said. The ice

had now been broken and Harry, quietly encouraged by Mr Towen, began to talk.

Adam, the potential officer, began to learn about the Royal Marines. Harry

explained the way Royals served on ships and why the four brigades of Royal

Marine Commandos, the 40, 41, 42, and 45, were the toughest fighting units in

the world. He went on to refer to Marine folklore, such as the tradition of

Jubilee Gate at the depot, the haunting ground of the ghost of a lost sentry.

MR TOWEN TAKES A HAND

Adam joined Harry on the scramble the following morning. He was a

natural athlete with plenty of cross-country training and once he had the hang

of it he found no difficulty in beating Harry round the course. But he could

never beat him by much distance.

No

matter how much he exerted himself Harry always managed to toil along two yards

or so behind. The next day it was much the same, save that Harry was unusually

silent and had pinched lines about his mouth. Afterwards they sat in the hedge

on the lane and drank coffee from a flask brought by Adam. Harry drank, handed

back the flask top, and broke his silence. “I’m in trouble,” he mentioned. “Had

a barney with Uncle Zach last night. Told him I’d fixed an appointment at the

Navy Recruiting Office for my medical and education test for the Royals. The

old man nearly went up in flames.” “Didn’t he know of your plans?” asked Adam. “I’d

only told you and Mr Towen,” said Harry. “That’s why I thought it time I told

Uncle Zach what was happening. Didn’t think he’d be so against it.” “Can he

stop you?” Adam inquired. “Is he your legal guardian or something?” Harry shook

his head. “No, he didn’t bother to take out court papers when he took charge of

me,” he said. “I don’t need anybody’s permission to join up. All I have to do

is produce death certificates of my parents.” “Then there’s nothing to worry

about,” said Adam relieved. “It’s too bad your uncle doesn’t approve, but he

can’t do a thing to stop you.” “That isn’t the point,” Harry said gloomily.

“Uncle Zach’s a funny old case, but he’s good to me. Brought me up when my

father died. I’ve got to think of his feelings.” “Why not think of your own?”

“You can’t throw over a career just because of your uncle. That’s too much for

anyone to expect.” “It’s a bit awkward,” Harry said glumly, and refused to say

any more on the matter. Adam guessed something of the conflict going on inside

him and was wise enough not to press the point. They talked of other things for

a while, then Harry mounted his bike and pedaled off to work. Adam went home

and made a report to his father. “It’s disgusting,” said Adam, highly indignant.

“That selfish old man is simply annoyed at the idea of doing his own

housework.” “Why shouldn’t he be?” Mr Towen quietly asked. “He’s raised Harry,

fed and clothed him. Surely the old man is entitled to a little consideration

for doing all that?” “I still think it’s selfish,” snorted Adam. “Why should he

stand in the way of Harry making something of himself?” “Most of us are

inclined to be just a little bit selfish,” said his father. “The old man’s

going to be rather lonely if Harry goes away. I don’t approve, but I can

understand. Anyway, it’s none of our business.” “I suppose you’re right,”

sighed Adam, watching Mr Towen pace the carpet. “Just nothing we can do about

it.” “Nothing at all,” agreed Mr Towen, pacing furiously, his teeth biting into

the stem of his pipe. “We’ve absolutely no right to interfere. “None at all,”

nodded Adam. “But if you wanted to see Harry, your car’s in the drive.” “What?”

said Mr Towen, halting and staring at him. “In the drive,” Adam repeated.

“Harry’s working on those repairs to the old Corn Exchange at Wotherton.

“Hurrumph,” said Mr Towen thoughtfully. Adam was grinning and presently a

twinkle entered his father’s eyes.

THIS CAN’T GO ON

Half-an-hour later Mr Towen was driving into Wotherton and pulling up at

the Corn Exchange. The old building was encased in a framework of metal poles

and the walls were dotted with busy figures.

Mr

Towen spoke to one of the workers on the ground and a piercing “Haree”

presently brought a slight figure swinging from the heights. “Morning, sir,”

said Harry. “Morning,” said Mr Towen and was suddenly puzzled as to what he

should say. “I was just passing and I decided to see how the work was getting

on,” he began. “You won’t know the place when we’ve finished, sir,” said Harry,

continuing to regard him with an inquiring expression that made Mr Towen

uncomfortable. “But it’s quite a job putting up scaffolding round these old

buildings.” “I should imagine it would be,” Mr Towen said vaguely. He felt like

kicking himself for coming because now he knew definitely that Harry’s business

was something in which he had no right to interfere. “All those nooks and

crooked walls,” Harry went on. “Would you like me to show you round, sir?”

“Some other time,” sighed Mr Towen, turning towards his car. “I’d better get

back and do some work.” He planted his tin foot on the running-board, then

glanced towards the watching youngster. “Good luck, Harry.” “Thank you, sir,”

Harry said steadily. Mr Towen drove back to the estate. “I felt a regular ass,”

he said ruefully, when telling Adam about it. “As soon as I saw Harry I knew it

was a mistake. It’s something that only he can settle and he has enough worry

on his plate without any well-meaning duffers interfering. Mr Towen busied

himself with his duties around the estate and gradually the matter of Harry

Clint was pushed into a corner of his mind. It would probably have stayed there

had not an incident brought it out into the open two days later. There was a

cattle mart in a town a considerable distance away on the afternoon of the day

following the meeting at the Corn Exchange. Mr Towen drove up there on business

for the estate. The business was concluded in the late evening and he had the

choice of putting up at a hotel or driving through the night. Mr Towen chose to

return and at

ZACH’S DECISION

At

“That

boy was a surprise to me, sir,” said the chief. “A regular caller here for the

two years I’ve had the office, and I was looking forward to signing him on. A

keen ‘un if ever there was one. Fixed his appointment for the medical, then

yesterday he comes in and says it’s all off.” “Chief, I want you to do me a

favour,” said Mr Towen. “It’s highly irregular and entirely up to you, but I

should like that appointment kept open.” “Why not?” said Bamford. “As long as

you can let me know the day before so’s the doctor doesn’t lose a day’s golf

for nothing.” “I’m obliged,” said Mr Towen. His next place of call was a small

house in a backstreet. The door was opened by a beefy elderly man, who bulged

and sagged in a collarless shirt and pair of overall trousers. He gazed

suspiciously at Mr Towen. “We ain’t buying nothing today,” he said, and tried

to shut the door. Mr Towen got his metal foot in the way in time. “It’s about

your nephew, Mr Clint,” he called, and the door at once swung open. The beefy

man reappeared, an expression of alarm on his face. “The lad ain’t in trouble,

is he, sir?” he said hurriedly. “Harry’s in no trouble,” Mr Towen said

reassuringly. “It would be easier to talk if you invited me inside.” Uncle Zach

worriedly agreed, and Mr Towen was led into the kitchen where a table was

littered with the remains of a meal. “I won’t keep you long,” said Mr Towen.

“I’d better make it clear your nephew doesn’t know I’ve come to see you. I wanted

to talk to you about his joining the Royal Marines.” “It’s just no good, sir,”

said Uncle Zach, shaking his head. “I’ve got my mind made up.” “But why?” asked

Mr Towen. “Don’t you think the services a good life for a man?” “A fine life,”

said Uncle Zach pleasantly. “I’d like to let Harry join. I’d miss him, of

course, but I’d get along. Only I know it wouldn’t be no good for him.” “I’m

afraid I don’t follow you,” said Mr Towen. “It’s young Harry, see,” said Uncle

Zach scratching his head and fumbling for words. “He ain’t right for it.” “Me

and Harry’s father,” went on Zach. “We’re big fellows, se. Harry’s pa was a

drayman and he could nigh hoist a horse on his shoulders. Harry ain’t like

that. Get him out on some of that Commando training and he would just fail to

bits.” “I see!” exclaimed Mr Towen, beginning to understand. “You think Harry

isn’t up to it.” “That’s right,” Uncle Zach replied. “I’m acting for the boy’s

own good.” Mr Towen almost laughed, then an idea came to him. “Put a coat on,

Mr Clint, I’m going to take you for a little drive,” he said. “I’ve got to get

to work,” Uncle Zach objected. “This is more important,” said Mr Towen. A coat

hung behind the kitchen door. Mr Towen grabbed it with one hand, Uncle Zach’s

elbow with the other, and hurried out to the car. Harry’s uncle was still

protesting when the car stopped outside Frankley Coppice. “We walk the rest of

the way,” said Mr Towen, guiding him through the gap in the hedge and into the

coppice. They followed the scramble route at a slow walk for a quarter of a

mile, using the easier route of stepping-stones across the stream and beginning

the climb of the far bank. Halfway up Uncle Zach halted and rested against a

tree. His face had turned purple. “I ain’t up to this thing, sir,” he wheezed.

“Ain’t there no easier way of getting where we’re going?” “Just up to the top

and down by way of that bog over there,” Mr Towen said. “That weak little

nephew of yours runs round twice every morning before going to work.” Cor!”

said Uncle Zach. Mr Towen relented and led Zach back the easier route to the

car. Uncle Zach fell through the door and collapsed, groaning, on a seat. “The

Marines turn out first class commando soldiers,” said Mr Towen, climbing behind

the steering wheel. “But they don’t just want hunks of brawn and muscle. They

want lads with brains and determination. I think Harry has all of those. He

drove into the town and let Uncle Zach off at the place where he worked. It had

been a silent journey. Uncle Zach spent most of the time fighting to get his

lungs into normal working order and the rest in heavy thought. The outcome was

a hurried visit by Harry to the Towen’s over the weekend. It was a wildly

excited Harry who could hardly wait to spill out the news. “Uncle Zach must be

going round the bend!” he gasped. “Got in last night and found the old man

darning his own socks. The first words he said were, ‘Maybe that ain’t such a

bad idea of yours joining the Marines, boy. It’s a fine life for a young man’.

Crikey, you could have knocked me down with a lamppost!” Mr Towen winked at

Adam. “What a stroke of luck!” he said.

MARINE CLINT

The next few days were long and lingering ones for Harry, then Tuesday

came and things started to move with a rush. Harry reported at the Recruiting

Office, had his medical, and was relieved to be passed as fit for service in

the Royal Marines; sat for an education test, completed various forms, and then

solemnly swore his Oath of Allegiance.

He

was handed his travel documents and went, hardly believing it was true, into

the street. Mr Towen had his car waiting outside and, together with Uncle Zach

and Adam, Harry was carried to the railway station. There was an hour to wait

for the train. Harry sat with the others in the refreshment room and passed the

time in a state of fidget. The train steamed in and Adam helped him load his

case aboard. “Maybe I’ll be in uniform next time I see you,” said Adam. “Watch

me chase you around if I do get my commission.” Harry grinned weakly and was

then drawn aside by Uncle Zach. The old man was immensely solemn and dignified

in a rusty black suit and paper collar and he was weighing his heavy turnip

watch in his hand. “It’s a good watch, lad,” he said, handing it over. “Ain’t

lost more than a minute a day in forty years. A man should have a good watch

when he’s going out into the world.” “Thanks, Uncle,” said Harry, tucking it

into a pocket. The instrument was the size of an alarm clock, but it was Uncle

Zach’s treasure and Harry appreciated the gesture. Harry scrambled for his

seat, then leaned through the window to shake hands. Seconds later the train

was moving and the little group on the platform was falling behind. Harry

changed stations in

© D. C. Thomson & Co Ltd

Vic Whittle 2006