BRITISH COMICS

(Rover

Homepage)

THE PUZZLE OF THE PURPLE SAND

Last episode

taken from The Rover issue: 1708 March 22nd 1958.

|

For New Readers:

In late 1939, the German dictator, Adolf Hitler, invaded Poland, and

Britain and France

declared war on Germany. The

rest of Europe was

neutral. Shortly after the start of the war, a British agent was working in a

German laboratory discovered a purple sand which he suspected the Germans

were using to manufacture an explosive of an atomic nature which could win

the war. Nicholas Wake, a King’s Messenger, was sent to find the source of

the sand. He traced it to an explosives factory in Poland,

where Zeppelins brought it from the south. Following the route of the

airships, Wake travelled south through Rumania,

crossed the Danube and

eventually landed in Bulgaria.

|

|

“It’s

a tough problem, but obviously I’ve got to get down to Yokaruda as quickly as

possible,” I told myself as I looked up from the map to the rugged Bulgarian

mountains before me. “There’s little chance of finding a car for hire in this

country. I must try to get a horse somewhere.” But I knew that at least a

hundred and fifty miles, much of it across wild mountainous country, lay before

me—with only a brief section of railway to help me on my way. According to my

map, I knew, too, that the Bulgarian roads are bad and scarce. And time was a

most important factor. Barren and grim the mountains looked in the moonlight. A

rough road ran towards them from the spot where I stood on the southern bank of

the Danube, in a Bulgarian

national costume. Barely ten minutes ago, I had left a small sailing boat in

which I had crossed the river I had parted once again from my staunch helper,

big David McKenzie. I had hired the boat at Rastu, on the Rumanian side of the Danube. Its

swarthy owner was really a British Secret Service agent, to whom I had been

guided by other British agents with whom I had managed to make contact in

Rastu. So, at last, the trail of the purple sand which in various disguises, I

had followed through Nazi Germany, then German-occupied Poland and Rumania, had

brought me to Bulgaria. My

last hope was that at last I was near the end of my search. It was vital that I

should discover the source of the mysterious purple sand with which Germany was

preparing a new and terrible explosive. The British Foreign Office knew that

before it was of any use the purple sand had to be found in sufficient bulk to

be mined, and that Germany alone

possessed a suitable source. It was my job to find out just where the source

was. I was certain that I was still proceeding in the right direction, for,

about three weeks ago, I had discovered the arrival end of the purple sand—a

secret factory in the Carpathian Mountains, on the southern frontier of Poland.

There I had also seen an airship mooring-mast, and had discovered that the

purple sand was brought from somewhere south by Zeppelins. Obviously I had to

find out the place from which those Zeppelins came. Hastening on southwards,

seeking more contacts with British Secret Service agents with helpful

information, I had learned that there were four night-flying Zeppelins on the

job, always passing due north and south. The most recent discovery was that

they had been seen passing over the Bulgarian towns of Vraca, Lozen and

Yokaruda. All of these towns were due south of each other. The trail obviously

led on to the south of Bulgaria.

Already I had encountered many dangers and difficulties. But always I had

managed to get in touch with British Secret Service agents in the most

unexpected places, and obtain help and useful information. Nevertheless, I

should more than once have been beaten but for David McKenzie, the big Scotsman

who had been appointed my helper by the British Foreign Office. I had just

parted from him. But I knew that it would not be long before I should be glad

to see him again. I had a feeling of triumph as I stood facing the Bulgarian

mountains, wearing the national costume, and with a Bulgarian passport and

money in my pocket. “So far, so good!” I exclaimed, folding up my map. “But

now, where am I to get a horse?” This was indeed a problem. I greatly hoped

that I should soon find some farm where I could buy one. Meanwhile, I realised

I must rest before I tackled the mountains, for the past twenty-four hours had

been both nerve-racking and strenuous. I lay down, thankful for my knack of

being able to fall asleep instantly at any time and in any place. Dawn, however,

found me well up in the mountains, following the rough road that wound through

great gorges. Anxiety filled me as I strode along. I knew it was forty miles of

terrible going to Vraca. My map showed me that if I had to walk all the way I

should lose much precious time. Not a soul did I see for over an hour. But,

suddenly, as I rounded a bend in the road, I saw before me a gipsy encampment

with numerous huge black tents, and the smoke of wood fires curled up

everywhere. Right before me, on the outskirts of the camp, a lean gipsy with a

face tanned to the colour of mahogany, sat on an upturned bucket, rolling

himself a cigarette and staring in front of him. What thrilled me was the sight

of a few tethered horses and donkeys. There was a rough but sturdy-looking

horse grazing near the fellow in front of me. In the end, I got the horse for a

sum in dinars equal to five pounds, with a saddle and bridle thrown in. Shortly

afterwards, I mounted briskly, filled with relief. “Yon road will take you to

Vraca,” were the gipsy’s parting words on learning my immediate destination.

“But you will have to pass through the valley of the Tombs. If you reach

nightfall, do not stop, I do not advise you to sleep there.” “Why?” I asked

curiously. “There are demons there,” he said briefly. “I’m not scared of

demons, even in the moonlight!” I grinned. But as I rode off, my heart beat

faster. The gipsy had hummed two bars of a tune. They were the opening bars of

“Oranges and

Lemons,” the British Secret Service code tune! The manner of his humming

theme—opening two lines repeated—warned me of danger. “So the Valley of Tombs is a

place to hurry through,” I muttered as I galloped on. “Thank you, gipsy.” Of

course, that gipsy had not guessed at my urgent errand for the Allies. He could

not know that I was a King’s Messenger, nor even did he suspect me to be

British. He hummed the tune on the chance that I might need a British secret

agent’s warning. I had no time to signal a reply to show that I understood. But

I was alert and wary as I rode on as fast as my horse could carry me. For

several hours I rode rapidly with few halts for rest. It was late afternoon

when I reached the Valley of the Tombs. It was an astonishing sight. Huge grey

tombstones, almost hidden by tall grass covered several acres of ground. As I

approached the nearest of the great stones, I saw that they were covered with

time worn carvings of horses and warriors and strange-looking writing. Although

I could see no sign of any living thing, I remembered the gipsy’s warning and,

urging on my tired horse, raced forward through the amazing valley at full

gallop. Nothing happened until I was half-way through the tombs. Then I heard

the crack of a rifle and the hum of a bullet as it whined past my head. Gasping

angrily, I flattened myself along my horse’s neck and urged it to its utmost.

Two more shots came from a different direction, and one passed through the

loose sleeve of my Bulgarian tunic. But I got through unharmed, and at last

galloped safely into the shelter of trees at the far end of the valley. I had

seen no one. The shots had been fired from the cover of tombstones by hidden

marksmen. Had I been on foot, or riding slowly, unwarned, I should have been

killed by these bullets fired by lurking robbers for the sake of any money I

might have had on me. I reached Vraca without any trouble about two hours

later, just as dusk was falling. It was a queer little town, semi-oriental in

appearance, with, here and there, domes and minarets rising above the huddled

mass of houses. But all that mattered to me was that Vraca was connected to

Lozen by a railway line. My map had told me that. I was dead tired after my

long, hard ride, but I dare not stop. Not without regrets, I sold my plucky

horse to a kind faced young peasant in the market place, who promised to look

after it well. I soon found the dingy little railway station in the centre of

the town. To my relief, I was told that a train—the second one of the day—would

be leaving for Lozen within half an hour. It did not leave for another two

hours. By that time, I was worn out with fatigue and impatience. It was only

eighty miles to Lozen. But that train just crawled along, and it was not until

the next dawn when I reached Lozen, at the foot of more mountains. It was

another small semi-oriental town. It was satisfactory to have reached the

second of the three towns through which I must pass. But the railway could help

me no further. From Lozen it crawled eastwards to avoid climbing the mountains.

How could I proceed straight southwards from there to Yokaruda? There was only

one answer. I must try to hire a car. After a search of nearly an hour and a

lot of bargaining, I managed to persuade the owner of a remarkable private car

to take me to Yokaruda. Two hours later, I was thrilled to see the houses and

spires of Yokaruda in a valley below us, and the old Turkish bridge that spans

the river on its western side. I felt well pleased when I paid off my driver in

Yokaruda market place. I had travelled across the whole of mountainous Bulgaria in two

days! Without rousing any suspicions, I had reached the southernmost place

above the Zeppelins had been seen flying at night, according to the information

given me by my “contracts” away back in Rastu, in Romania. Now what? I must

surely be near the end of the trail of the purple sand! For, quite close, in

the mountains south of Yokaruda, lat the frontier of Grecian Macedonia. And

beyond Greece lay

the Mediterranean! I did not think

I should have to search much further. Hungry, I entered an inn near the market

place, and found it was kept by an old, grey-bearded peasant, who was helped by

his sturdy son. Here I brought a flask of wine, a large sausage and a loaf of

rye bread. At This vital stage I dare not ask about airships. I dare not risk

arousing the interest of Nazi agents now! From the innkeeper’s son, I merely

inquired casually if the mountain passes and paths through to Macedonia were

all clear of snow yet. “Yes,” he whispered, with a strange look, “and I can

guide you by a short cut through the mountains, by which it is possible to

avoid all the dogs of Customs officers and all Customs houses,” he added. He

had evidently mistaken me for somebody interested in running smuggled goods on

a big scale. My pulse leaped. If I had a local guide, my task might be a lot

easier. But I dare not risk it. I gave him a vague answer and soon left the

inn.

THE PIT OF THE PURPLE SAND.

There

was a small moon when I climbed eagerly up into the mountains some hours later.

The track I was following was rough, but I was by then accustomed to long

tramps across mountains. I was sure that I had slipped out of Yokaruda

unnoticed. But several times I halted and turned abruptly, to make sure that I

was not followed. My good luck still held. Nevertheless, I proceeded cautiously,

straining my eyes ahead as the trail climbed and wound upwards. I wanted to

avoid frontier Customs posts, and I felt sure that this well worn track must

lead to one, eventually. About an hour later, I halted on a mountain shoulder

and looked around anxiously. “I must have covered about three miles,” I

muttered. “So, according to the talk at that inn, I can't have much further to

go. Yet my map tells me that the Macedonian frontier is only seven miles south

of Yokaruda. If I’ve got to cross the frontier it will mean finding some

little-used path. I almost wish I’d accepted that guide—“I broke off short and

stood rigid, staring at the object that had just caught my eye. A great,

gleaming object was rising above that mountain top a little ahead of me and to

my right! It seemed to float in the air like a ghost, brightening as it rose.

It was a Zeppelin! My heart leaped as I saw that long, silver shape like a

giant cigar, soaring upwards, increasing speed. It swung round as I stared at

it. I crouched down behind a boulder as it turned to come in my direction.

Rising from five hundred feet to a thousand feet, it came right over me a

moment later. I had marked the mountain top behind which I had seen it rise.

Instantly, leaving the track, I ran towards the spot, slipping and stumbling on

the steep ground. “That Zeppelin rose less than two miles away from me!” I

gasped excitedly. “It came from right behind those crags yonder!” How, in the

next twenty minutes I didn’t fall and break my neck I don’t know, for, as I

raced along the uneven ground, I had keep my eyes on my objective. But, at

last, breathless, my heart pounding madly, I approached the crags I had marked.

Cautiously, I dropped to my hands and knees and crawled the last fifty yards.

Then at last reaching the jumble of crags, peered round them. I had counted on

seeing something of vital importance. What I saw took my breath away. It

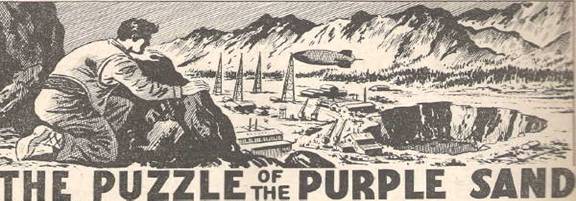

exceeded my highest hopes. I was looking down into a wide, moonlit valley. In

the bright moonlight, I could plainly see four airship mooring masts away

below. There was a Zeppelin moored to one, the other three were vacant. I saw

wooden buildings around them. About a hundred yards nearer to me I saw many

more buildings and numerous cranes, derricks and other machinery. Near them was

a black, yawning hole about fifty yards in diameter, with lights moving inside

it. I knew that at last I had found Germany’s

source of the purple sand. Near the pit, awaiting shipment in an airship, I

could see great piles of wooden cases. They were just like the cases I had seen

in the secret factory away back at Panok in the Carpathians. Without doubt they

were all full of the deadly purple sand, awaiting dispatch. I could see men

swarming round the buildings and passing in and out of them. I reckoned that Germany

employed at least five hundred specially-selected men on this job. This was

reckoning without guards. There was no visible fence round the workings nor the

airship landing ground. But I could make out sentries posted to keep intruders

away. To the south stood some crumbling walls, probably once the boundaries of

farming fields, some abandoned peasants’ huts and beyond these a belt of trees

probably concealing more guards. At last I had the information that was so

vital to the Allies, the news which was so anxiously awaited in London. “Can

the Allies get hold of this purple sand?” I asked myself. “Germany must

have leased this valley from Bulgaria, and

will have to be ousted somehow. But a force can’t be landed in a neutral

country to drive them out!” My thoughts ran on. If the Allies could seize this

purple sand pocket, how could they remove the stuff? The only way would be to

take it down by motor lorry to the nearest port—Salonika—there

to be loaded into ships. No other way would be possible, since the Allies did

not maintain airships of the kind suitable for heavy transport, and ordinary

aircraft would not be of any use for several reasons. But that problem could

wait. “I’m going down to Salonika at

once!” I exclaimed. “From there I can cable a report in code to London.” I

reckoned to proceed along the track up which I had come until I reached the

frontier Customs post, where I would merely show my Bulgarian passport and

personal possessions and ask the best way down to the nearest Greek town

according to my map. But I never reached the track! As I made my way round a

spur of the mountain, a startling thing happened. A dozen men leaped up from

behind boulders all round me. A dozen rifles covered me. My good luck had

apparently broken!

HELD FOR RANSOM!

For

a moment I was dumbfounded. Rage filled me as I faced my ambushers. Never had I

seen such a cut-throat gang. At one glance, however, I knew them for what they

were—Macedonian bandits from over the border. It was a maddening situation. I

had at last succeeded in my task of gaining the information that the Allies so

badly wanted. A speedy report was vital—and I was held up by a band of

brigands. Robbery could be the only motive for stopping me. With this

realization, I boldly faced the gaunt ruffian who seemed to be the bandits’

leader. “If it’s money you want, well, you can have all I’ve got on me. But

leave me my report and let me proceed at once. I have urgent business. To my

dismay, the scoundrel shook his head and laughed. He gave me a mocking bow. “I

do not speak well the Bulgarian tongue,” he said in a Greek dialect, naturally

believing me to be a Bulgarian. “I do not know what you say, Hands up, your

money or your life! I regret that I must detain you.” “For what?” I exploded.

“For a ransom,” he leered. “A gentleman who carries so much money on him, as

you do, surely has wealthy friends who will gladly pay highly for his release.”

At that, my fury knew no bounds. It was unthinkable that I should be held

captive by these scoundrels—indefinitely—when every moment of my time was

precious! I started to bluster and argue. It was no use. At a sign from their

leader, the gang closed in on me. Just as I wondered how they could possibly

know I had a big sum of money, I saw in their midst a fellow I recognised. It

was the son of the innkeeper at Yokaruda—the rascal who had mistaken me for a

tobacco smuggler—and had offered to show me a secret path through the

mountains. All was clear. The young ruffian had caught a glimpse of my

well-filled wallet when I had paid my bill at the inn. He had kept watch on my

movements, then had slipped across the border to there brigands with news of a

wealthy traveler and brought them after me. I was quite helpless, and at once

the brigands started to force me through the mountains to their secret lair.

That journey by way of twisting mountains, with my captors leering at me,

seemed endless. In vain, I argued with the bandits leader and assured him that

he would never get a ransom for me. He did not believe me. “I will give you

three days to change your mind!” he laughed grimly. Three days! I did not mean

to be held prisoner for one day if I could help it. But dawn came, and still I

had no plans for escape. I was desperate. All day I was kept bound in the inner

cave, guarded by a rifle armed bandit, one hand being freed for a short time,

only so I might eat. My first guard was a huge glum-looking ruffian who smoked

cigarettes incessantly. He was surlily silent. He was changed after about three

hours as were his successors, most of

whom proved quite willing to talk. My guard had been changed again at

dusk. Once more I had the big, surly fellow. He sat with his back against the

cave wall, his rifle across his knees, smoking. A lantern hung on a nail above

his head. From the outer cave came the sound of talk and harsh laughter, and

the red reflection of a cooking fire. I sat pondering. But suddenly I was

alert, listening tensely. I stared at my huge guard in amazement. He was

humming quietly the tune of “Oranges And

lemons.” It seemed incredible. But I knew I was not mistaken. This giant bandit

was actually humming the British code tune—the six opening lines which as good

as told me that everything was going to be all right! I looked at him closer as

he puffed cigarette smoke into the air. Realisation dawned on me. “David

McKenzie!” I gasped. It was big McKenzie guarding me, in bandit garb, his rifle

across his knees. How he had taken the place of the real guard I did not know.

It was enough that he had turned up once again in amazing fashion. He gave no

sign of recognising me, until the talk and laughter in the outer cave died

down. Then he rose, quietly cut my bonds with a knife, handed me a pistol, then

beckoned me to follow him. We tiptoed froth into the outer cave, gripping our

weapons. All was silent. I caught my breath as, by the light of a lantern

hanging near the cave mouth, I saw a dozen bandits lying asleep round their

fire. McKenzie motioned me to creep round them. Fifteen minutes later, thanks

to the two ponies which McKenzie had hidden nearby, we were well clear of the

lair of the sleeping bandits. Though pursuit might start at any time, I did not

want to leave the neighbourhood of my big discovery too hastily. While held

prisoner by the bandits I had had ample time to ponder over the source of the

purple sand. It had filled me with dismay to realise that the Allies would have

great difficulty to make use of it. How could they do so? I was still grappling

with the problem when we halted our ponies on a broad stretch of path some

miles from the bandits’ lair. “I’ve found the source of the purple sand,

McKenzie!” I announced. “You have?” he exclaimed delightedly. “Where—” “My

knowledge would have been no use, if you hadn’t turned up once again and

rescued me,” I broke in. “How did you manage that?” “Oh, I’ve been following

you round—lost you in Yokaruda,” he laughed shortly. “But I picked up your

trail again after those bandits had collared you.” I told him how I had seen a

Zeppelin soaring up from one of the mountains two nights ago, how I spotted the

place from where it had risen, and thus found the air ship mooring ground, and

the vital sand pocket and workings. “But how can the Allies possibly use the

purple sand?” I muttered. “They’d have to use force against Greece and Bulgaria, and

that we know they wouldn’t do. McKenzie nodded glumly. “It comes to this—the

Allies can’t possibly use the pocket of purple sand themselves!” I exclaimed

grimly. “We can’t allow Germany to

continue to use it for her new weapon,” McKenzie declared. “There’s only one

thing to be done. We must destroy it.” “I’ve thought of that,” I assured him.

“But how?” For answer, he grinned and showed me that his saddlebags contained

several hand grenades. He had stolen them from a police station in Yokaruda, he

told me, thinking they might come in handy. That was after he had learned of my

capture by the bandits, and had thought he might have to bomb his way in to my

rescue. But he had changed his plans on noticing that one bandit was about his

build. He had knocked this man out and taken his place. Immediately we formed a

plan. If we could get into the valley, we might blow up the whole workings. Two

or three bombs bursting inside that purple sand pit would blow it skyhigh,

together with any Zeppelins that happened to be anchored to the mooring-masts.

A few minutes later, we were ready to set out for the valley. “But there are

guards,” I pointed out thoughtfully. “Our best way of approach would be through

the wood on the valley’s south side. We’re on the right side now. But there are

sure to be one or two sentries lurking in that wood. “Leave them to me!”

grinned McKenzie, and we urged our ponies forward. Within an hour, we were

approaching the wood on the south side of the valley. Here were more of the long

crumbling walls I had seen before. We dismounted behind one and tied our ponies

to a bush. McKenzie motioned me to wait. A moment later the moon vanished

behind a cloud and he promptly disappeared through a gap in the wall with all

the silence of a Red Indian. I don’t know how long I crouched by the wall,

waiting, revolver in hand in case of accidents. The moonlight came and went

fitfully. Suddenly I heard a few bars of “Oranges and

Lemons” whistled softly. The next instant, big McKenzie was back by my side.

“All’s clear now!” he whispered. “Fill your pockets with bombs, then come

along, Hurry!” We both grabbed bombs from the saddlebags and a moment later, we

were creeping through the little wood. We stole through it unchallenged.

McKenzie had done his work well. On the farther fringe of the wood I saw the

great airships floating almost above us, and once again saw all the buildings,

derricks and other machinery. I could see, too, the yawning mouth of the sand

pit about a hundreds yards away from us, almost surrounded by big buildings and

machinery. It was now past midnight, and

all was silent. But I knew that in those buildings and huts were about five

hundred men and I could see other guards patrolling some distance away. Next

instant we were creeping through the towering machinery. Suddenly we dropped

flat as three rifle armed guards came along and passed within a few feet of us.

I realised that there were guards everywhere. Even worse was the sight of a

wire fence round the pit, doubtless electrified, and previously invisible in

the gloom. Let’s get at it before more guards come along,” I whispered.

McKenzie nodded and we had not covered two yards before one of the trio who had

passed looked back. He saw us, and leaped towards us with a challenging shout. Even

as a rifle cracked and a bullet hummed between us. I saw McKenzie rushing at

the wire fence, and heard shots from all sides as men roused by the rifle crack

came dashing from buildings. Ducking, I followed him as more bullets whizzed at

me. Then we heard a crash, glanced back, and saw running men falling all ways

as my grenade exploded with a flash and a roar. But almost instantly a siren

wailed from somewhere overhead. The whole valley was roused. Everywhere,

yelling men were hunting for us; shouts and shots showed that we were seen. I

saw black objects hurtle from McKenzie’s hand. He was hurling his grenades over

the electrified fence into the sand pit. Joining him, I heaved a couple. Then

we turned and ran for our lives. We twisted and dodged through the gaunt

machinery and huts, while the whole valley echoed to the din of the siren, the

shouting of our pursuers and rifle fire. But, suddenly, mingled with the din,

there sounded a series of explosions from away down inside the sand pit. Our

grenades were exploding there! At that moment, we were clear of the buildings.

Hearing the thuds, we dropped prone. Roars burst from our pursuers. But the

next instant the whole world seemed to explode in thunder and flame. From out

of the sand pit leapt a fifty-foot column of coloured fire. The earth rocked to

the mighty detonations. Vaguely I heard shrieks followed by thunderclaps

overhead, then a fearful crashing of things falling. For a nerve racking moment

we lay still. Dazed, we staggered to our feet. The moored Zeppelins had

vanished, blown to atoms! Nearly all the buildings were wrecked and blazing and

over all hung a great cloud of smoke, a huge blazing crater showed where the

sand had been, and everywhere tottered the gaunt wreckage of tangled machinery.

The only known pocket of the purple sand had been destroyed for ever! McKenzie

and I ran from the place, now unpursued. We tore through the wood, reached our

ponies, and galloped off. Ahead of us across the mountains lay Greece and a

triumphant return to London.

“Well

done!” Sir John Saunders nodded to McKenzie and me when he had heard the whole

story. “So Germany will

never use the purple sand against us, What you two have achieved for the Allies

will never be forgotten!”

THE END

THE PUZZLE OF

THE PURPLE SAND 6 episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1703 – 1708 (1958)

© D. C. Thomson & Co Ltd

Vic Whittle 2004